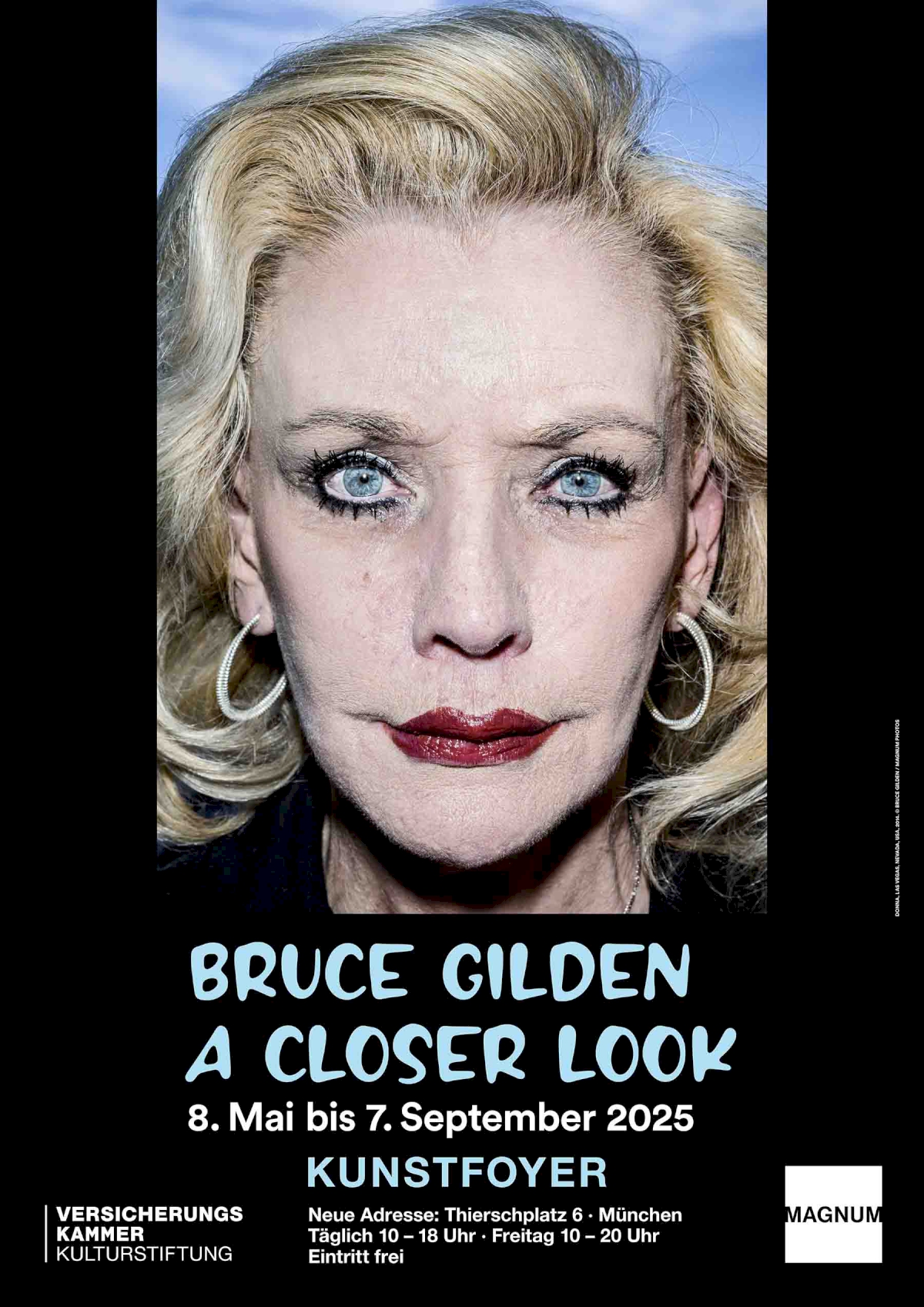

Bruce Gilden

A Closer Look

With May comes renewal!

Starting May 8, 2025, we continue at our new location at Thierschplatz 6 in Lehel with the exhibition of the renowned New York street photographer BRUCE GILDEN.

Our new opening hours from May 8 are as follows:

Daily from 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM, Fridays from 10:00 AM to 8:00 PM.

We look forward to welcoming you soon at our newly designed Kunstfoyer at its new location, Thierschplatz 6!

Since 1995, the cultural commitment of the KUNSTFOYER exhibitions by the Versicherungskammer Bayern has been part of Munich's museum mile. The curatorial focus lies primarily on photography retrospectives and topics related to the world of film. After a short exhibition break (August 2024 – April 2025), the Kunstfoyer has moved from Maximilianstraße 53 to Thierschplatz 6 in Munich and continues to be a reliable venue for thought-provoking thematic exhibitions showcasing significant artistic positions. A former pizzeria has undergone a structural metamorphosis to become an exhibition space for everyone: the Kunstfoyer welcomes all visitors with socially relevant themes—free of charge. To date, around 100,000 people have visited the three exhibitions held each year, with over 300,000 digital visitors accessing our website in the same time span. We aim to build on this success with our future exhibition program.

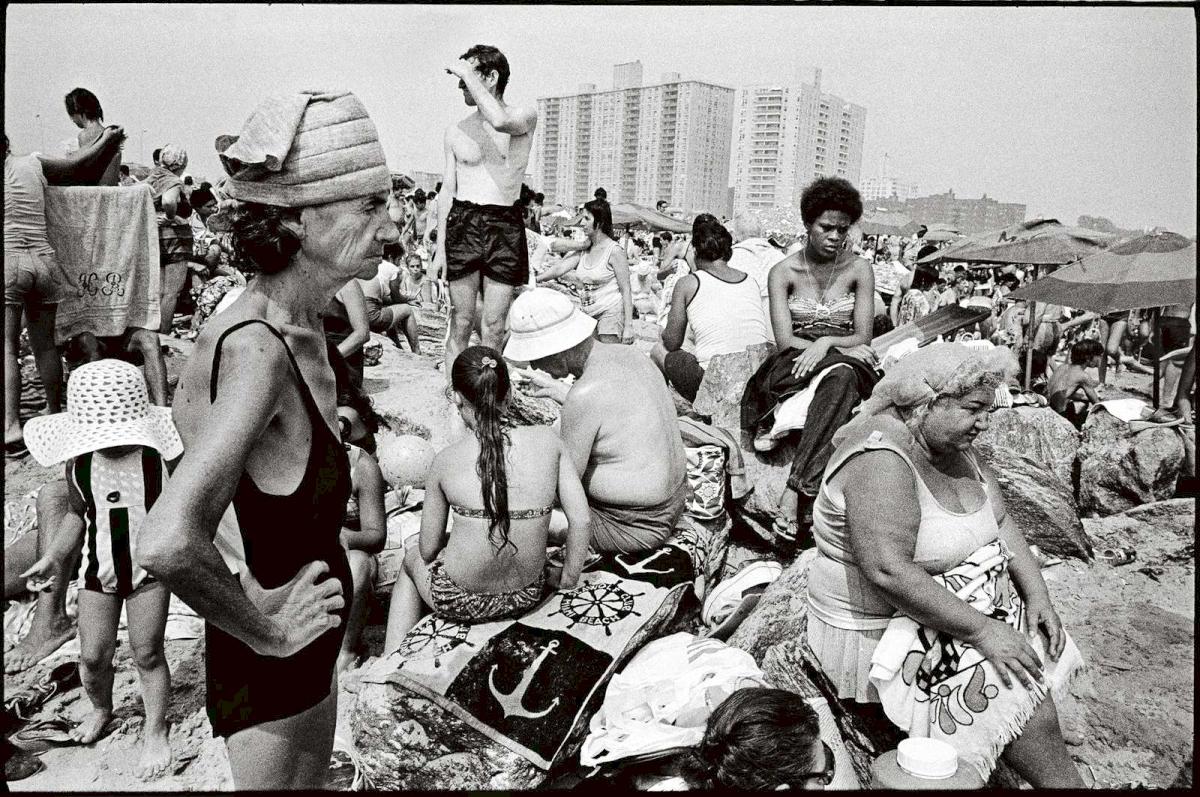

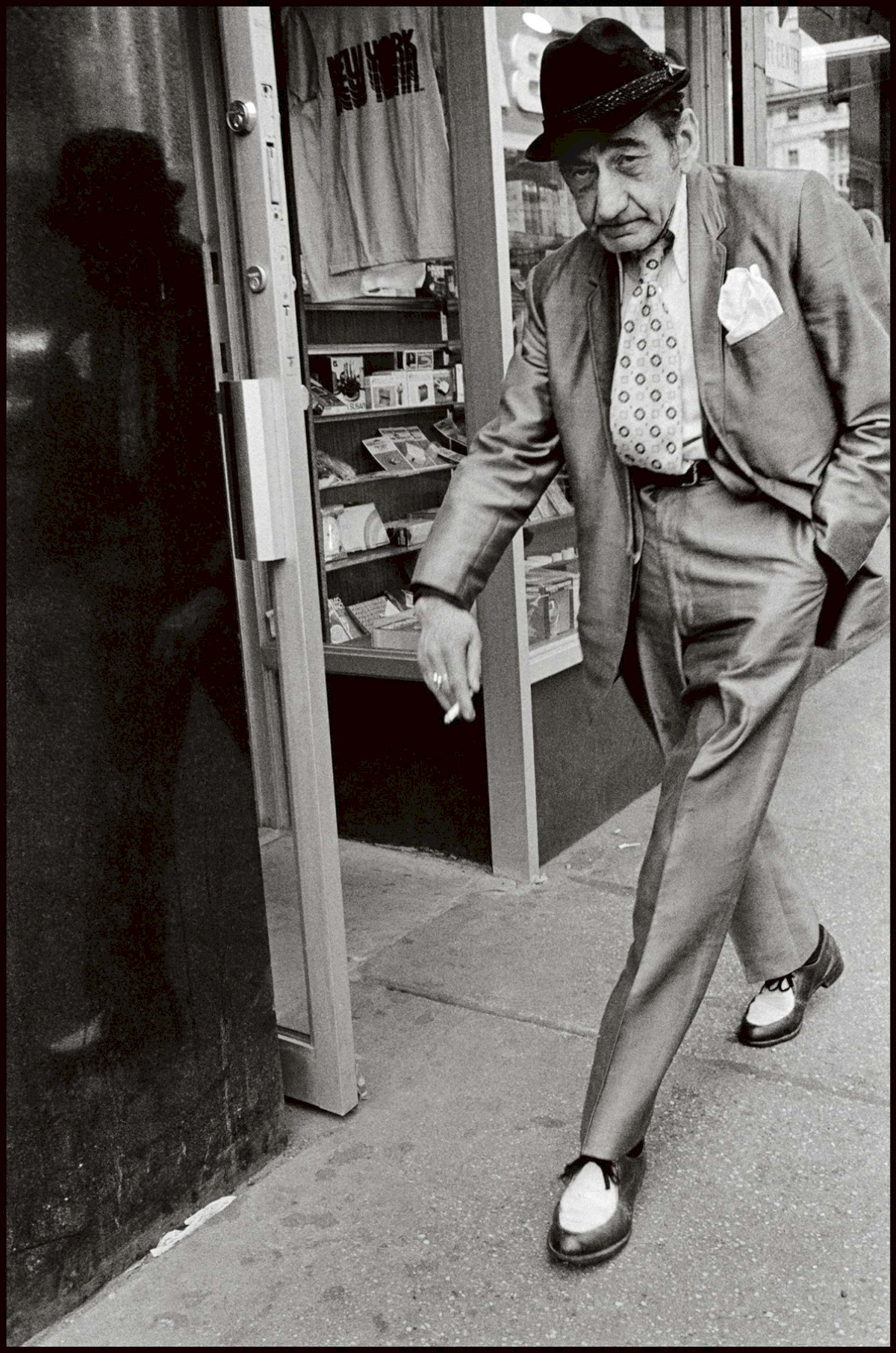

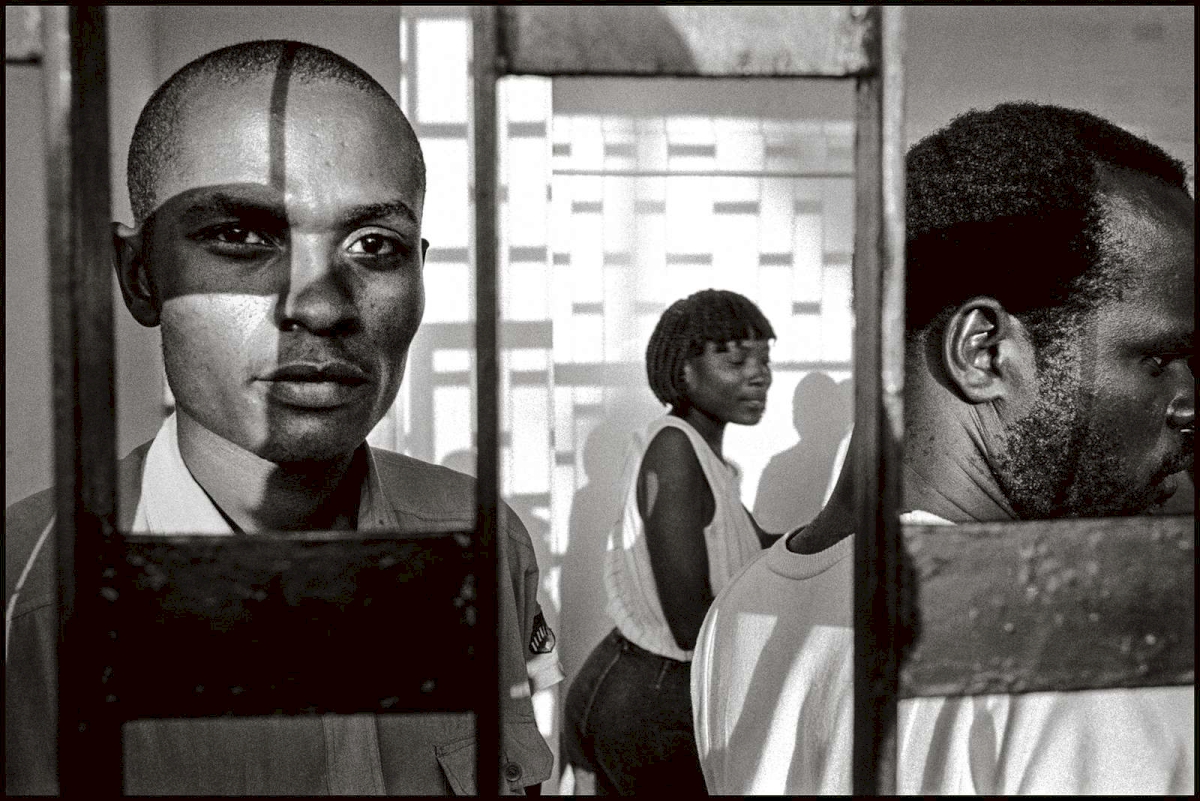

Starting May 8, 2025, we will adopt a transatlantic change of perspective in our newly designed city-center exhibition space: most recently, we showcased photographs and photo reportages by the 14 current female Magnum photographers. Now, also from the legendary Magnum agency, comes the world-renowned street photographer and portraitist Bruce Gilden. The exhibition was conceived by Isabel Siben in collaboration with Bruce Gilden: it presents 50 black-and-white street photographs taken since 1969 in locations such as Coney Island, New York City, Haiti, Japan, Ireland, London, and Paris. In addition, 22 large-scale portraits—so-called “faces”—are featured, unleashing monumental power in the space through their authenticity.

Bruce Gilden (*1946 in Brooklyn, New York) has spent the past 5½ decades roaming and working on the streets of countless cities—and has been an official Magnum photographer since 1998. From the beginning, he has directed his gaze toward the peripheries, the precarious realities that society prefers to overlook. For him, the subjects worthy of depiction are not stars, celebrities, or self-proclaimed influencers. He is interested in the “invisible,” the “underdogs” and “misfits”—those living on the margins of society, often noticed only by street workers or emergency services. But Bruce Gilden is no moralist.

To enhance understanding of his work, two interpretive essays by Freddy Langer and Max Blagg are integrated into the exhibition. Most importantly, the artist's own commentary is not to be missed: Bruce Gilden explains his approach in the “cinema” space of the Kunstfoyer, as well as on the 360-degree tour of our website and on YouTube.

Public tours are conducted by photo historian Hans-Michael Koetzle. A catalog in the format of a “deck of cards” will be published to accompany the exhibition “Bruce Gilden. A closer look.”

Biography

Bruce Gilden was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946. After briefly studying sociology at Penn State University he quit college and decided to become a photographer in 1967. Aside from taking a few evening classes at the School of Visual Arts in New York, Gilden largely considers himself to be self-taught.

Although Gilden started his career photographing on the sidewalks of New York City where he grew up, he has since made significant bodies of work in Haiti, Japan, England, France, Ireland, India, and the USA. Along with his acclaimed personal projects, Gilden has worked on numerous commissions for clients including Louis Vuitton, RATP Parisian transportation system, Dolce & Gabbana, Gucci, Balenciaga, and on assignments for Vanity Fair, GQ, Vogue Homme and New York Times Magazine.

Gilden is the recipient of many awards and grants for his work, including several National Endowments for the Arts fellowships, the New York State Foundation for the Arts, Japan Foundation Artist Fellowship and in 2013 a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship. Since the seventies, his work has been exhibited in museums and galleries all over the world.

Bruce Gilden has published more than 30 books of his work: From Facing New York in 1992, to Coney Island, GO, Face, Lost and Found, Cherry Blossom, Black Country, as well as most recently The Circuit and Haiti.

Gilden joined Magnum Photos in 1998. He lives in Beacon, New York.

On Bruce Gilden - By Freddy Langer

Can one do such a thing? Step into the path of passersby and thrust your camera onto their chest, as if it were a loaded weapon—which, strictly speaking, it is? Kneel before them to shoot from a frog’s-eye view? Or shamelessly keep clicking while they lie helpless on the ground, or lost in private conversation, or swept away in ecstatic rapture? Yes, you can. Legally, this has been settled. At least, one can do it in the name of art. And to document the goings-on in public spaces as well. Anyone stepping outside must therefore reckon with becoming a subject. It might happen from ambush, unnoticed, from a distance. Or from up close. Very close. Which, to some, may feel like an assault.

Discretion is the last word that comes to mind when thinking of Bruce Gilden’s work.

He doesn't hold back. He charges straight at his subjects. Pounces like a predator on its prey, as if New York’s Fifth Avenue were a hunting ground. His images, he says, are not secretly stolen. On the contrary, he gets so close to people that they could physically touch. “If your pictures aren’t good enough,” Bruce Gilden loves to repeat a quote from Robert Capa, his former Magnum colleague, “you’re not close enough.” Some may still call it theft. But Gilden insists: the fact that people notice him, that they register his presence, gives him the license to photograph them. And sometimes, rumor has it, he even spins them into a better pose with a quick hand movement. You wouldn’t be surprised to hear that this occasionally leads to trouble, especially since he sometimes flashes people directly in the face, using the blinding burst to underscore the city’s raw energy and the strain of its hurried inhabitants. One wonders how often a fist might have landed square on Gilden’s nose.

Gilden has a ready explanation where this fearlessness — occasionally bordering on aggression — comes from. His father, slick-haired with massive rings and wads of cash stuffed in his pockets, ran a tire shop in Brooklyn. At least, that was the official version. But the first time young Bruce entered the store, there wasn’t a single tire in sight. The business was a front, the father a gangster. Gilden grew up—if not in the criminal underworld, then in its shadows, surrounded by small-time and big-time crooks. In that environment, restraint and timidity weren’t virtues. It was a tough education. Gilden doesn’t know fear. “I learned how to move in that world.”

At first glance, one might think Bruce Gilden is out to expose the world’s dark side: the threatening, the uncomfortable, the other. His photos often depict precarious conditions, frequently showing lives on the edge. The word “downfall” lurks like a watermark glimmering beneath many of his images. “Crime” is another. He moves freely among crooks, in the U.S., in Russia, England, and Japan. Sometimes it's the Mafia, other times the Yakuza. Gilden’s motto: stay completely deadpan. Just make sure not to let their strange mix of refinement and brutality faze you. He faces gangsters eye to eye. And knows how to turn their arrogance to his advantage. They coolly pull knives and guns from their pockets, playfully jab fingers into each other’s eyes or pry open mouths flashing a dozen gold teeth or one blackened gap next to the other. Blood trickles from a hand. They lift shirts to show off their tattoos. Or dangle matches, cigarettes, fat cigars from their lips like they’re eager to fulfill every cliché. Bruce Gilden could romanticize them. But he has no interest in mythmaking. And although he gets incredibly close, he never watches like an anthropologist studying foreign rituals. He observes like a natural scientist through a microscope, watching single-celled organisms twitch and move. Without the least empathy.

And then there are the cast-offs. People who believe fate owes them something, hoping for fast money at the racetrack, only to lose everything. People in Haiti, swinging between despair, bliss, and ecstasy during voodoo ceremonies. Bruce Gilden has visited the country sixteen times, a nation perpetually in chaos, one of the world’s poorest. But it wasn’t poverty that fascinated him, it was a surprising level of contentment. The result: confusing, enchanting, and frightening images. With their radical aesthetic of layered planes, extreme wide-angle distortion, and jarring blurs, they seem ripped from dreams rather than grounded in reality. Then there are the revelers at Mardi Gras in New Orleans, disguised to the point of spooky eeriness, or so naked that only the tiniest scraps of fabric cover them, if any at all. Which makes it even scarier. Gilden paid less attention to the parades on Bourbon Street than to the crowd of onlookers. What happened among them in the beginning. What happened to them later on. It shows that year after year, he’s moved further and further away from classic street photography altogether. Away from photo reportage, if you will. And closer to faces. To reactions. To emotions. To portraits.

Street photography shows us what we usually overlook in our everyday tasks, in the bustle of the city. It captures moments in which the photographer sees the world momentarily arrange itself into a perfect composition, into an image symbolizing a mood, a state of mind, an array of connections otherwise lost in the chaos of daily life. This moment is fleeting, gone in the blink of an eye. But the photographer carves it from the whirlwind of a Thousand impressions surrounding him. Unlike a painter who builds an image piece by piece, the photographer is closer to a sculptor—one who subtracts. The world is his block of marble. The viewfinder is his chisel. He doesn’t invent; he reveals. Just as Michelangelo supposedly said of his David: that the figure had always been inside the stone, merely waiting for someone to release it. It had always been there in the Carrara quarry; no one had simply noticed it before. All Michelangelo had to do was chip away what didn’t belong.

Can one do such a thing? Get in people’s faces—literally? Come in so tightly that the faces of those who do not meet the usual ideal of beauty burst the frame. Exposing their every flaw in unbearable, almost painful clarity? Pimples, warts, scars. Swelling, drooping eyelids, crooked noses. Sunken cheeks, twisted teeth, stubble on women’s faces. Not that they’ve given up. Many of the women wear layers of makeup, lipstick smudged into exaggerated kisses, eyeshadow slathered on like leeches, details made even more grotesque under Bruce Gilden’s merciless flash. He says: the older he becomes, the closer he gets. So close, you can see the pores. And yes, he can do that too. Because he asked. He spoke with these people, spent time with them, listened to their stories. Gilden calls them “collaborative portraits.” And through the large-format prints and the way they’re presented, he passes on to us what his subjects gave to him: the license to stare. And isn’t the human face, as naturalist and writer Georg Christoph Lichtenberg once said, “the most entertaining surface on earth”? Though he didn’t believe faces could be read. On the contrary, he wrote that nothing of a person’s nature could be gleaned from their exterior.

The same applies to many of the individuals Bruce Gilden selected for his “Face” series as well. He finds them at state fairs, for instance, but more often in the much rougher corners of cities like Las Vegas, Miami, and Columbus, Ohio. There, he found farm boys beside the unemployed, drug addicts beside prostitutes. Banal faces, Gilden says, have never interested him; by which he likely means the faces of the saturated, leveled-out middle class. He seeks out those who are different. People who stand far apart from the usual crowd. But what he shows often crosses a line - one cannot politely call it “character” any longer. Impossible to overlook the consequences of alcoholism, poverty, and domestic violence, all etched into these physiognomies. These people have seen much and expect little. They show it without reserve. “If you can’t smell the street,” Bruce Gilden once said, “it’s not street photography.” Paraphrased: If you can’t smell the sweat, it’s not a portrait. Some call his series a freak show. Bruce Gilden sees it as a gallery of individuals. And often tells their stories alongside: Being raped by grandfather. A childhood spent in an orphanage. The pill addiction from botched prescriptions. “Only God can judge me,” reads the tattoo on one woman’s body. That look into society’s abyss deserves to linger. Even if it’s hard. Because you meet sharp stares that cut deep. That pierce like blades. And are hard to withstand. If we would call the body nature, then our faces are our social front. Mirroring our learned behavior. All the more impressive, then, that none of these people freeze into expected masks, stage themselves, or censor their appearance in front of the camera. The calculated play of facial expressions—what one might call facial choreography—seems entirely alien to them. That’s what makes them appear so radically authentic.

If his earlier black-and-white street photos, with their blur, distortion, flash-burned details, and maverick perspectives, echoed the aesthetic of Expressionism, these recent color portraits recall the grotesques of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the harsh portrayals by German painters like George Grosz and Otto Dix who distorted the likenesses of both wealthy industrialists and prostitutes. But perhaps they come even closer to the faces from Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymus Bosch, and other Renaissance artists who gave us an idea of what the sick and outcast looked like back in their plague-ridden times.

But it wasn’t art history that brought Bruce Gilden to these people. Let’s say it clearly: it was his own story that brought him there. Memories of a mother who suffered under his father’s violence, beatings and lit cigarettes pressed to her skin. A mother, who brought strangers into the bedroom in the afternoons. Who, in the end, was institutionalized for drug addiction. Where she took her own life. That was nearly fifty years ago. Bruce Gilden was thirty. Only now does he speak about it openly. He says he’s lived much of what his subjects have lived. That he identifies with them. He bluntly calls his work catharsis. He calls those he portrays his family. And he calls these portraits: images of his life.

Übersetzung: Peter Stephan Jungk