Helmut Newton. Polaroids

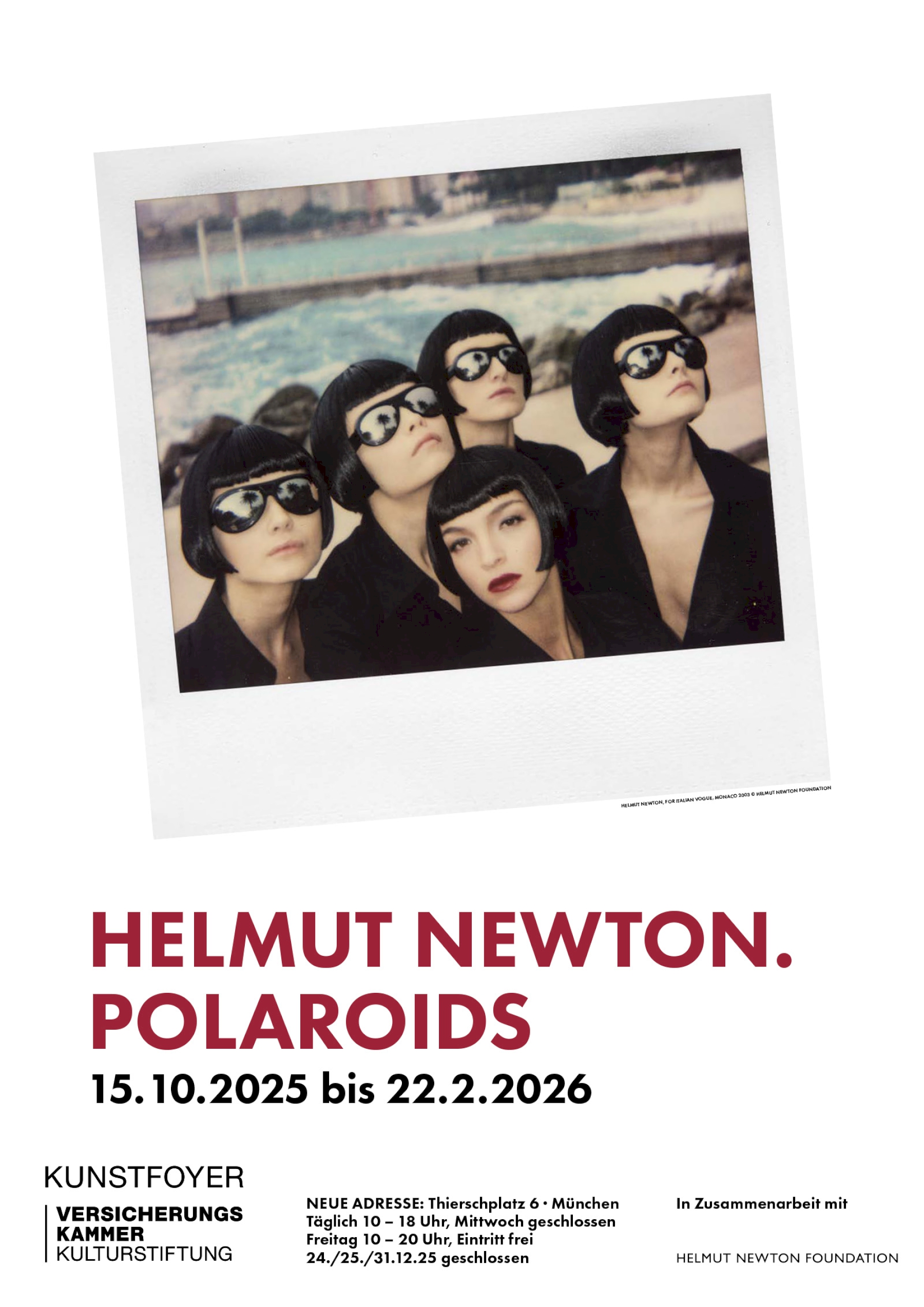

From October 15, 2025, the Kunstfoyer of the Versicherungskammer Kulturstiftung in Munich will present the exhibition Helmut Newton. Polaroids. The show highlights iconic instant photographs by the renowned photographer, capturing Newton’s unmistakable style in a spontaneous medium.

Since the 1960s, the Polaroid process has revolutionized photography. Already in 1947, Edwin Land had developed instant photography for his company, the Polaroid Corporation, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Subsequently, the process was tested and continually refined by many renowned photographers on behalf of the company. This led to the first exhibitions, a dedicated artistic support program, and the foundation of the Polaroid Collection, which, of course, also includes several works by Helmut Newton.

Anyone who has ever used such a camera will remember the smell of the developing emulsion, the speed of the image’s appearance—in short, the fascination with the instant photograph. With the particularly popular SX-70 camera, the Polaroid developed on its own, since the developer and fixer chemistry was already embedded in the photographic paper, and the picture was ejected from a narrow slot at the front of the camera. Other Polaroid systems, by contrast, required an additional fixer liquid to be spread across the image surface. In almost all cases, however, the finished picture could be held in one’s hands immediately after exposure, allowing the image composition to be reviewed at once. In this respect—though not technically, but in terms of spontaneous availability—the Polaroid may be regarded as a forerunner of today’s digital photography, whether on the displays of smartphones or digital cameras.

Polaroids are in most cases unique objects. Only certain film types, especially black-and-white Polaroids, also produced negatives, which some photographers enlarged into small editions of silver-gelatin prints. For some, the Polaroids served as visual studies; for others, as independent artworks. In nearly all areas—advertising, landscape, portrait, fashion, and nude—and in almost every part of the world, this unusual image-making technique found enthusiastic users since the 1960s, in both applied and artistic photography.

Helmut Newton, too, made intensive use of various Polaroid cameras, especially during his fashion assignments. Behind this was, as he once admitted in an interview, his impatient urge to know immediately how a situation would look as a photograph. For him, the Polaroid was like a sketch of ideas, while at the same time serving to check lighting conditions and image composition. Often, just a few Polaroids sufficed for his first assessment; only in his Naked and Dressed series for Vogue did he consume the material “by the crate,” as Newton put it.

The exhibition at the Kunstfoyer of the Versicherungskammer presents Newton’s work in roughly equal parts: individually framed SX-70 or Polacolor prints and mounted Polaroid enlargements—more than 150 works in total. Since the 1960s, Newton photographed with different Polaroid cameras and also used instant film backs that replaced the roll film cassettes of his medium-format cameras. Looking at his Polaroids—which often marked the beginning of a fashion image concept and in which his incomparable visual fantasies manifested— we can study the creative ideas that were later fully realized in the final, photographer-approved image. Two examples here also illustrate the different stages of development: from a photographic sketch (via Polaroid) to the final picture, which Newton then shot with an SLR camera on “real” film, as he always said. Thus, while walking through the exhibition, one may also stumble upon the backstories of other iconic images Newton later published in his books, which have inscribed themselves into our collective visual memory. In this sense, the current presentation is akin to looking into the sketchbook of one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century.

In 1992, Newton published Pola Woman with Schirmer/Mosel—a highly unusual book devoted exclusively to his Polaroid photographs. The publication was, in his words, “particularly close to my heart,” but it also sparked controversy. To the accusation that the images were not perfect enough, he countered: “That was precisely what was exciting—the spontaneity, the immediacy.” Subsequently, some of his Polaroids also appeared in magazines, and today signed originals are traded at high prices on the art market. Posthumously, in 2011, the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin published another volume of his Polaroids with Taschen.

Equally interesting and revealing are Newton’s handwritten notes on the image margins: occasional comments on the model, client, or location and date. These annotations, along with the traces of use and signs of wear, can also be found on the enlargements included in the exhibition. They testify to a pragmatic approach to working materials that now possess their own autonomous value. Above all, the unique aesthetic of Polaroids—their unpredictable shifts in color and contrast—makes this experimental technique fascinating even today. Newton used his Polaroid cameras for decades across almost all genres of his work—least of all in portrait sessions. Some of the small-format originals he gave to clients and models to secure their “cooperation,” as he put it. Most, however, he guarded like a treasure, which is now preserved in its entirety in the Foundation’s archive.

A display case additionally presents a range of smaller-format Polaroid cameras from a Berlin private collection. Their variety in form, design, and equipment reflects the playful approach to the medium and its popularity. And the fascination with this extraordinary technology continues to this day, even if the successor films by “Impossible” are often said not to match the quality of the original Polaroid material. Resourceful contemporary photographers seek out the last remaining, long-expired original material on the market and experiment with it. Such contemporary Polaroids—often serial, in tableau form, or abstract—constitute unique prints with a singular visual reality. Helmut Newton, however, primarily used Polaroid material as a means to an end, yet with his photographic sketches he always arrived at outstanding, self-contained image solutions.

Matthias Harder

Director, Helmut Newton Foundation, Berlin